NYT Archives Article

June 25, 1998, Thursday

Section: Circuits

Downtime; Transfer of Records to CD's Takes as Much Labor as Love

By Charles Bermant Dick Rosenquist of Saratoga, Calif., has unusual musical tastes, ranging from Maori sounds from New Zealand to the more obscure John Philip Sousa tunes, but many are unavailable on compact disks. So rather than listen to his old LP records, he is developing his own series of custom disks.

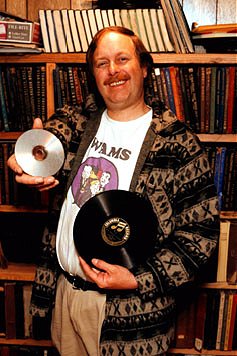

Dick Rosenquist of Saratoga, Calif., has unusual musical tastes, ranging from Maori sounds from New Zealand to the more obscure John Philip Sousa tunes, but many are unavailable on compact disks. So rather than listen to his old LP records, he is developing his own series of custom disks.

It took a CD-rewritable drive, custom software and much patience. "I was amazed at what I could do," he said. "I was able to put several old custom-made records on CD and enjoy them for the first time."

A day's drive north, in Silverton, Ore., a music collector, Gus Frederick, is seeking to transfer portions of approximately 7,000 old 78-rpm jazz records to CD's. "I really like this music," he said. "And it is extremely unlikely that any of it will ever be reissued on CD."

The technology for recording CD's is another step toward allowing people to have the music they want, when and where they want it. For instance, when Beatles albums were released on CD's, they followed the British song sequences, which confused many American listeners. As a result, the only way to enjoy a CD copy of "Yesterday and Today" or "Beatles '65" is to make it yourself.

The gear is available. The drives cost as little as $300 each and are starting to appear in some personal computers as standard equipment. External drives are compatible with either PC's or Macs. Software like Adaptec's Easy CD Creator Deluxe (www.adaptec.com) or CeQuadrat's Just Audio (www.cequadrat.com) allows users to record from a variety of sources and create a custom CD. Users can also develop their own sequences, eliminate surface noise and even design custom labels or jewel box inserts.

A homemade CD sounds better and lasts longer than the average homemade tape, but a CD is harder to make. A tape can be easily started, stopped, rewound and reused, while the CD recording and noise reduction process for an album can take several hours. The user may need to spend three or four times as much time as the length of the music being recorded to make a successful CD. And that does not take into account planning and learning time.

"This is not something for your average weekend PC user," said Mr. Frederick, who works as an instructional specialist and Web designer for the Oregon Public Education Network, which provides Internet resources to state schools. "People have the conception that it is like a cassette deck, but it's not that easy."

Because the process takes so long, you wouldn't want to tackle a large record collection. Even if one could spend the hours it took to complete a disk each day, it could still take more than three years to convert a collection of 1,000 LP records to CD's (one CD can contain several albums).

Creating your own CD's can also cross a legal line. Certain Pioneer and Philips drives designed for recording music comply with the Audio Home Recording Act of 1992 because they are not able to make a copy of a copy. The drive manufacturers also pay a royalty to music publishers. But drives that are predominantly designed for data storage on CD's do not have this restriction (and do not pay the royalty). So the duplication of copyrighted music on such drives is technically illegal. But "the record companies have never gone after consumers," said Cory Sherman, general counsel for the Recording Industry Association of America, "and it is unlikely that they will in the future."

Another use for this process is the personal adaptation of rare recordings. For instance, one music enthusiast in the Minneapolis area, Paul Packard, has several recordings by a local band called Chameleon, which featured Yanni, then unknown. And Mr. Frederick converted a one-shot record of comedian Stan Freberg made in 1959 in honor of the Oregon Centennial. (It was played in his household when he was growing up, so Mr. Frederick made a CD of the rare recording and presented it to his mother as a gift.)

If either Mr. Packard or Mr. Frederick sold these rare disks, they would owe Yanni and Mr. Freberg a percentage. But as long as a disk is intended for home use, it seems unlikely that any artist would deny a fan the privilege to enjoy rare music or comedy.

Recording CD's takes a state-of-the-art computer, as it requires a hefty hard disk and a large chunk of RAM, so you can't press an old, power-anemic PC that was sitting around unused into service and install it next to the tape deck and CD player. In most cases, an external recordable drive is attached to the computer, while a sound source -- turntable or tape -- plugs directly into the computer's sound card. (The best way to copy music from an existing CD is to use the installed CD-ROM drive for playback.) The quality of the stereo amplifier is not as important as the quality of the installed sound card, Mr. Packard said. He recommends that anyone who wants to make good recordings upgrade to a 64-bit sound card, which generally costs less than $100.

Those who want a custom CD and can't buy or install all that troublesome gear can order from services such as Custom Revolutions (www.customdisc.com). You can create a custom sequence of available songs and don't need to worry about copyright, but the selection is limited.

The average PC user would probably be happy with Mr. Packard's machine: a 200-megahertz Pentium equipped with 32 megabytes of RAM, but he uses words like "slow" and "taxed to the nth degree" when describing its performance when he is making a CD.

Mr. Frederick makes do with a 110-megahertz processor, but he has added a 2-gigabyte hard drive dedicated to the recording (in the processing phase, each minute of sound requires 11 megabytes of temporary storage). He emphasizes the importance of regular disk optimization for the process to work smoothly.

(During regular use, data from the same file may be scattered throughout the disk. So disk optimization, part of the Windows system, rearranges the data contiguously, allowing the computer to find the information faster.) "You are dealing with some massive files here," Mr. Frederick said. "So it's very important that they are not fragmented."

TAPE is still more convenient, but recording a CD is becoming easier to do. The newer software allows real-time correction of surface noise, eliminating the lengthy clean-up process, which can tie up your machine for hours. Manufacturers say that users can operate other applications while a recording is being cleaned up, but Mr. Packard disagrees. "If it crashes, you need to start all over again," he said.

And there are unexpected pitfalls in recording CD's at home. You may inspect what was once a grand LP collection only to find items that you were once unwilling to sell at garage-sale prices but haven't really missed. The albums left standing may include some work by obscure artists who have yet to make it to CD (e.g., T-Bone Burnett and Charlie Dore), custom records by friends or relatives (Tru Fax and the Insaniacs or Coco and the Lonesome Road Band) and some bootlegs (for shame!) or autographed items. You don't want to throw them away but don't want to listen to them with any frequency.

Add the fact that a full album from the pre-CD days may still have some standout tracks but that those in between -- which you learned to like because you were too lazy to get up and skip ahead -- sound impossibly dated. It then seems like a good idea to sample one or two choice cuts from each relic for an archival disk, in a "Best of the Rest" sequence. The good news is that you can change the running order and print cool labels. But the result will still hardly become part of your primary playlist. It becomes akin to a novelty anthology, to be listened to occasionally. The result might be the same if the records were left in the basement.

There is also the danger that once you get around to converting various oddities to CD, some other media platform will emerge down the road.

"No technology will last forever," Mr. Rosenquist said. "But CD's provide archival capability in a convenient package. You can't guarantee that it will always be around, but if something better comes along, then we'll have the opportunity to transfer it to the new medium."